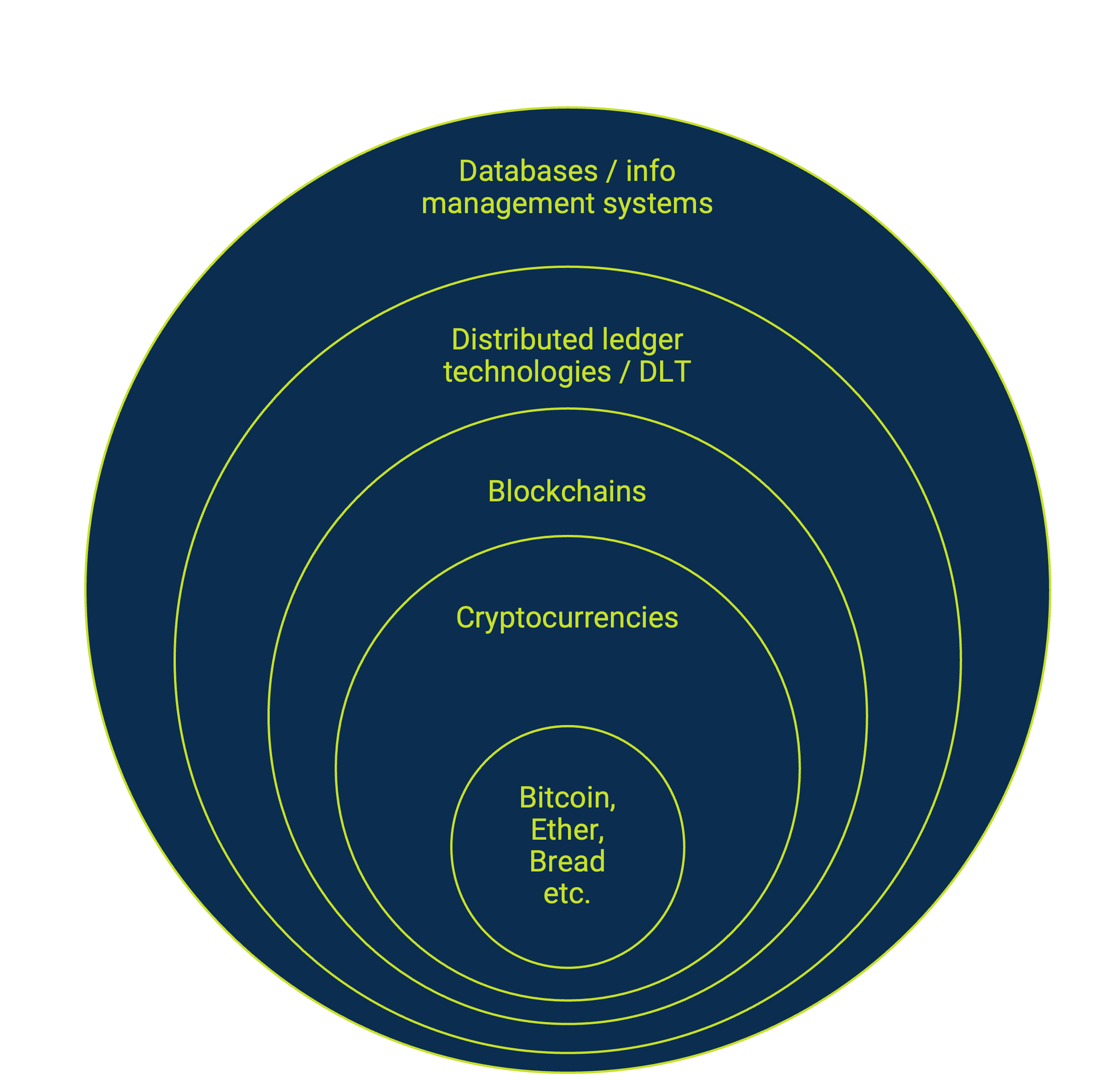

A blockchain is a type of distributed database system for managing information that can reduce the need for central authorities or trusted intermediaries to oversee interactions and make sure the network rules are being followed. This enables participants to engage in peer-to-peer data and value transfers, and potentially, to contribute to the design, functioning, and management of the network – i.e. to build networks based on multi-stakeholder governance. Blockchains are a subset of distributed ledger technologies (DLT)—ie. all blockchains are distributed ledgers, but not all distributed ledgers are blockchains.

In a blockchain network, identical copies of a database are stored on multiple computers, resulting in a single, shared ledger that records the history of interactions and asset ownership in the network, and maintains the rules governing interactions. This distributed structure leads to a lot of discussion about the extent and value of decentralization, but beware the hype: decentralization could refer to many different things, like the distribution of hardware, software, or decision-making power. Distributed computing power is not the same as distributed political power.

In a blockchain, data is arranged into “blocks” that are “chained” together using advanced cryptography, hence the name blockchain and the nickname “crypto”. It is extremely difficult to secretly modify or delete records once they are added to the chain, so blockchains are often said to be “immutable” or tamper-evident (as in, everyone knows if anyone tries to tamper with the record). This means users can have high confidence in the integrity of the shared data.

Cryptocurrencies

As well as managing information, blockchains can issue their own “cryptocurrencies” (eg. bitcoin on the Bitcoin network, or ether on the Ethereum network) that enable peer-to-peer value transfers and are used to reward participants for helping maintain the blockchain ledger. To maintain agreement about the “true” state of the shared ledger without a centralized authority, blockchains use a “consensus mechanism” that combines cryptography with game-theoretic incentives (eg. payments or penalties paid in cryptocurrencies) in ways that maximize confidence in the integrity of the ledger.

Blockchains can be public or private, permissioned or permissionless. In permissioned chains (often used by corporate entities), access and functionality are strictly controlled. In public networks like Bitcoin, Ethereum, Polygon or Solana, anyone with an internet connection can participate, in principle.

New societal governance mechanisms?

Information management is a critical part of modern societies. Since blockchains enable a wider degree of participation in the design and management of computer networks (relative to typical modern systems), and since cryptocurrencies can be programed to incentivize specific kinds of cooperative behavior, blockchain networks expand the scope to build sophisticated, large scale networks outside of traditional structures. For example, they make it possible to build transnational networks that are difficult, though not impossible, for governments to control, because states tend to assert regulatory authority via centralized bureaucracies or trusted intermediaries.

Related Concepts

- DAOs - Organizations using blockchain

- Primitives - Blockchain provides organizational primitives

- DeFi - Decentralized finance on blockchains

- Governance - Blockchain-based governance systems

- Transparency - Transparency enabled by blockchains